Bernie Wrightson has long been nicknamed “Master Of The Macabre.” But for the Inkwell Awards and ink artists, it should be “Master Of The Brush And Pen.” Few if any of his era exemplify that moniker more.

Born on October 27, 1948, Wrightson said, “I wish my mother could have waited until Halloween[;] that would have been perfect.” He credits a few different things for his love of the macabre and unique vision: growing up next to a cemetery, three visits from a headless ghost at age four, Catholic school, EC horror comics and old monster movies. (He went by “Berni” for years due to an olympic swimmer having the same name, then changed it back.)

Wrightson pored over the work of his favorite artists (and top inkers) like Graham Ingels and Jack Davis. “I’m more of a combination of Ingels and Davis than anyone else…sometimes [I] deliberately draw in the style of Graham Ingels,” he said in 1975. That is where he first learned inking technique. From Davis, he learned more techniques as well as humor. Bernie’s first published work was a letters page illustration for Warren Publishing’s Creepy #9, 1965, foreshadowing his future.

Wrightson’s only formal art education was a local TV program and one year of the Famous Artists Course advertised in Silver Age comics.

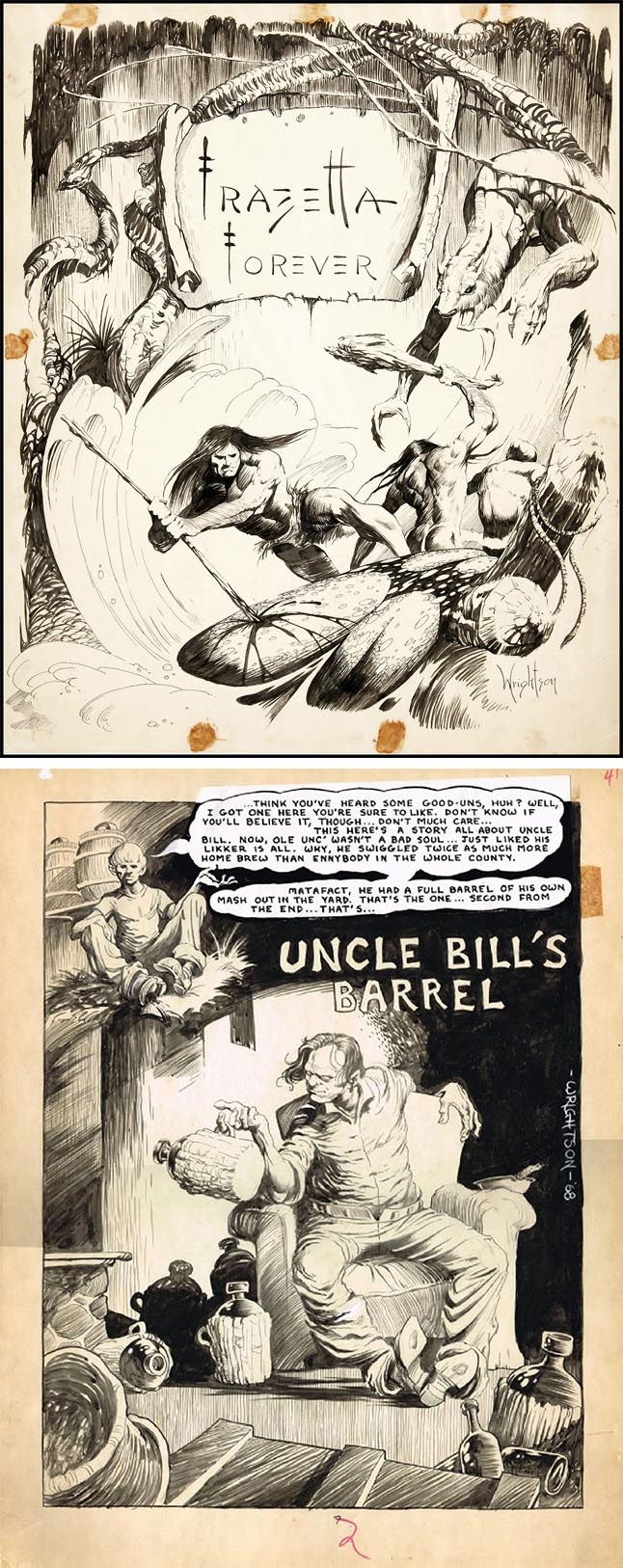

After an editorial cartoonist/production job at the Baltimore Sun newspaper, Bernie travelled in 1967 to NYC for his first convention, meeting future friends and collaborators Michael Kaluta, Jeff Jones (later Jeffrey Catherine Jones) and others. Bernie also met his “art god” Frank Frazetta, who offered encouragement. The con introduced him to “fan art,” and began his many contributions to amateur and semi-pro publications like Spa-Fon and others over the next few years.

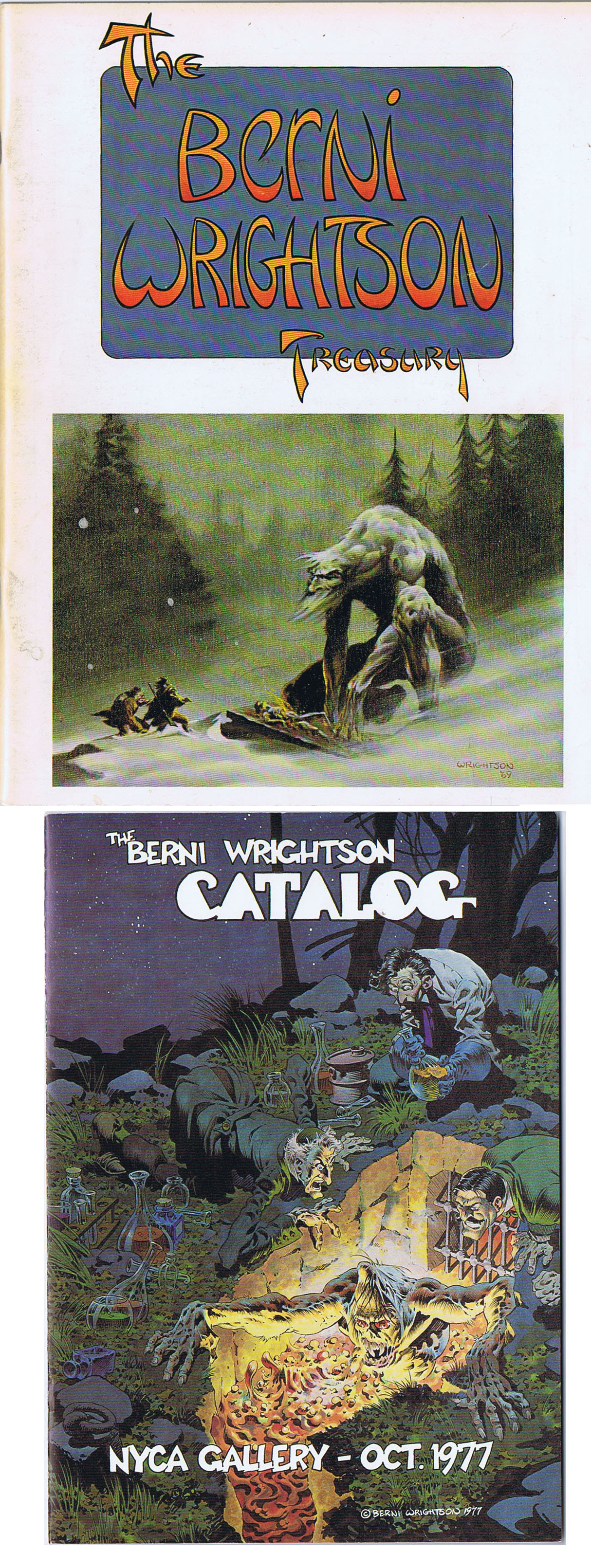

A year later at another con, Wrightson’s “Uncle Bill’s Barrel” fanzine work grabbed the attention of former EC artist/Inkwell Hall Of Famer Al Williamson, who brought him to DC editor/HoFer Dick Giordano, who took him to publisher Carmine Infantino. Impressed, they offered the 19-year-old his own book to draw, the Showcase debut of “Nightmaster.” But the intimidated Wrightson’s early work wasn’t quite ready. The issue was given to another artist (Bernie pencilled and inked the next two Nightmaster tales, but he lost interest).

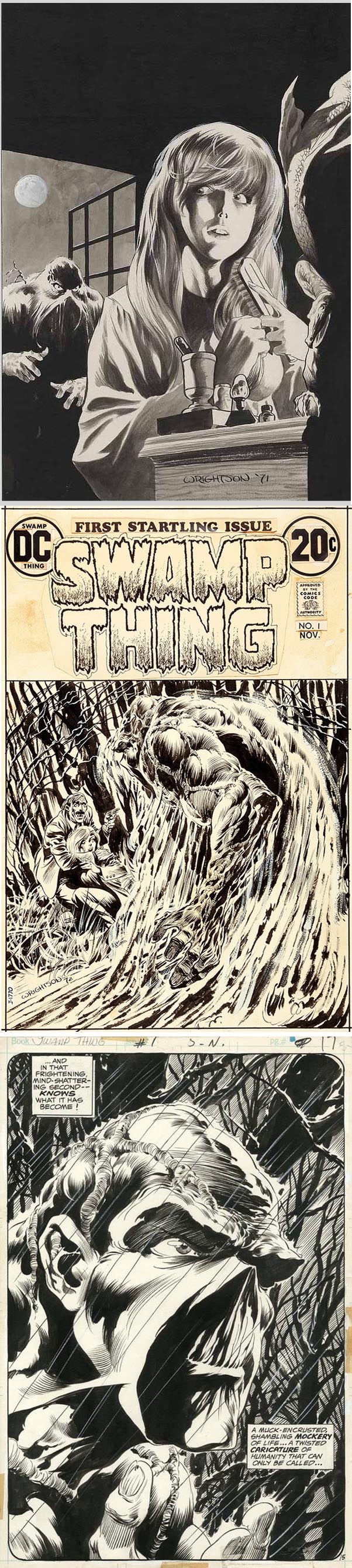

Instead, Wrightson was given introductory pages, covers and short tales for former EC artist-turned DC-editor Joe Orlando’s “mystery” titles like House Of Mystery (Bernie’s first work appearing in #179) and House Of Secrets. Both were perfect for Wrightson’s growth and technique with lush brush strokes for lighting effects and atmosphere. He credits Orlando as a mentor.

Wrightson and friends were enlisted to create material for Web Of Horror, a magazine-format comic book designed to compete with Warren’s Creepy and Eerie. It lasted three issues before the publisher closed up and left town (with Bernie’s cover and work for issue #4).

Bernie stayed busy. He teamed with Vaughn Bode for five watercolor-painted strips of “Purple Pictography” in the men’s magazine Swank. Then came occasional contributions for Esquire, National Lampoon, and other publications where Wrightson used myriad

color and b/w techniques.

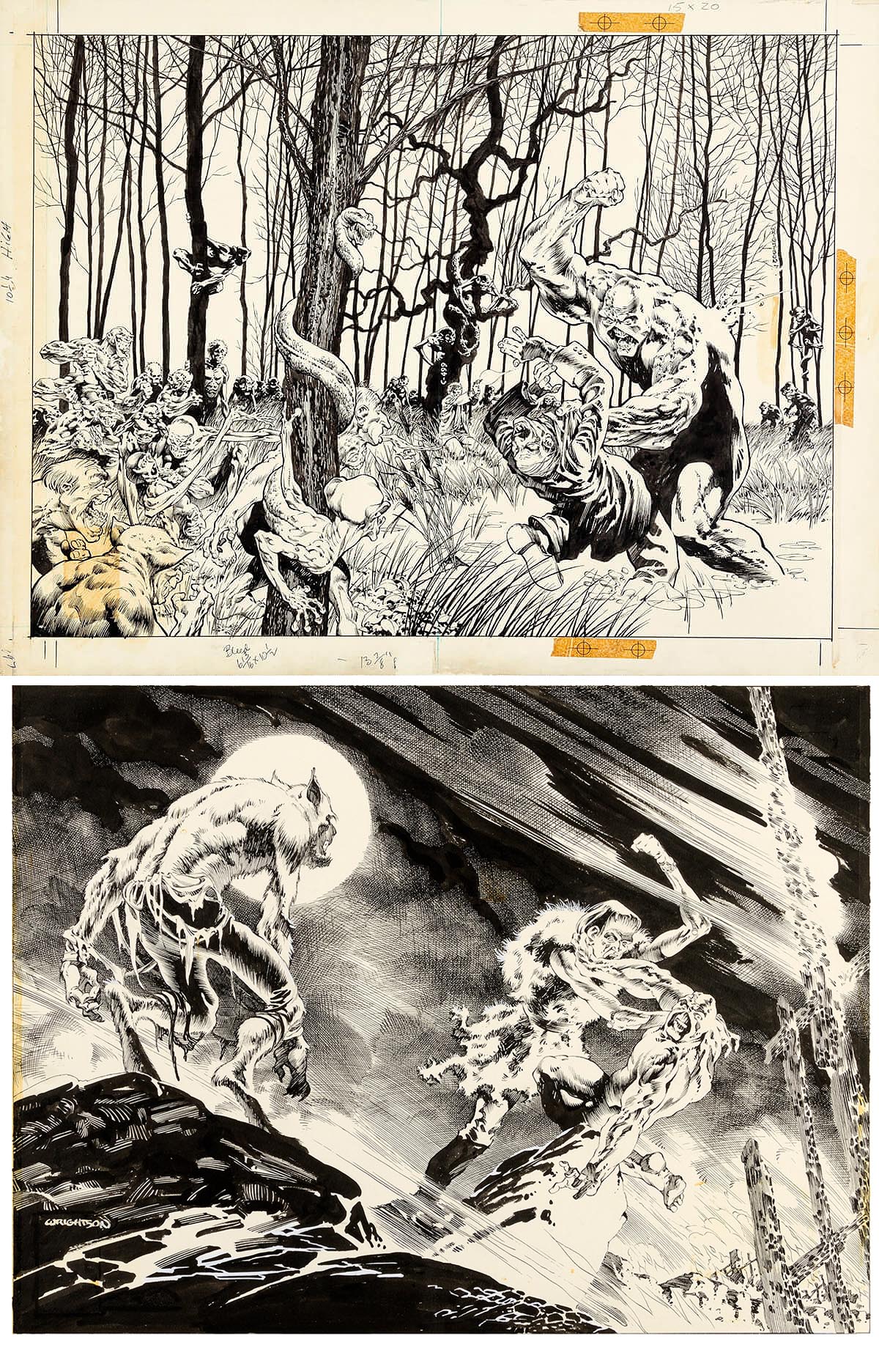

One of Bernie’s and writer Len Wein’s DC stories, “Swamp Thing,” became the cover and lead tale of House Of Secrets #92. It outsold everything and the character was awarded his own title. Their 10-issue run, though plagued by deadline pressure (and Bernie’s fading interest), became a classic and propelled Bernie to comic-book stardom. He won many awards for that and other DC books like Plop #1. Len Wein said, “…back in the days of Swamp Thing, he had the best ink line in the business.”

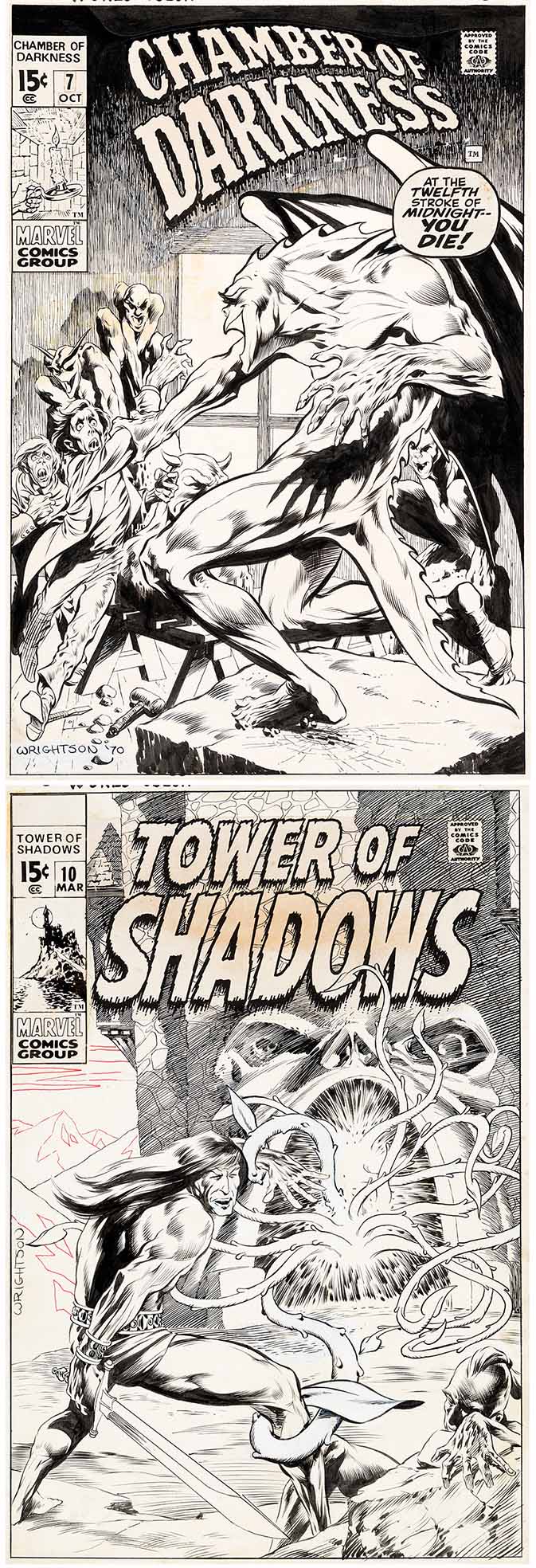

Lured by better page rates and the promise of coloring his own work, Wrightson moved to Marvel in the early ’70s but it didn’t last. Other than some notable covers (usually over others’ layouts) for their monster comics, the first comics appearance of Robert E. Howard’s King Kull and some story inking, he left in disappointment due to editorial interference and creative differences.

Tired of the deadline pressure and lousy print quality of color comics, Wrightson found a welcome home at Warren. Founder/publisher Jim Warren raised Bernie’s page rate from $65 per page (pencils and inks, at DC) to $110 and was the first publisher to return his original art. The freed artist shined in pen, brush and wash for horror tales both original (some written by Wrightson himself) and adapted from classics by Edgar Allan Poe and H.P. Lovecraft.

Bernie elucidates: “The whole [Swamp Thing] series, #1-9, [was] inked with a brush. And one of the reasons I got out of color comics was, you’ll notice issue 10 was done with a pen, and there’s a big difference, stylistically…inking with a brush had become too easy and I got real suspicious of that. I started seeing myself repeating little things with a brush and that frightened me…I was doing it without thinking. So I threw all my brushes out and started drawing with a pen…a lot of penwork.”

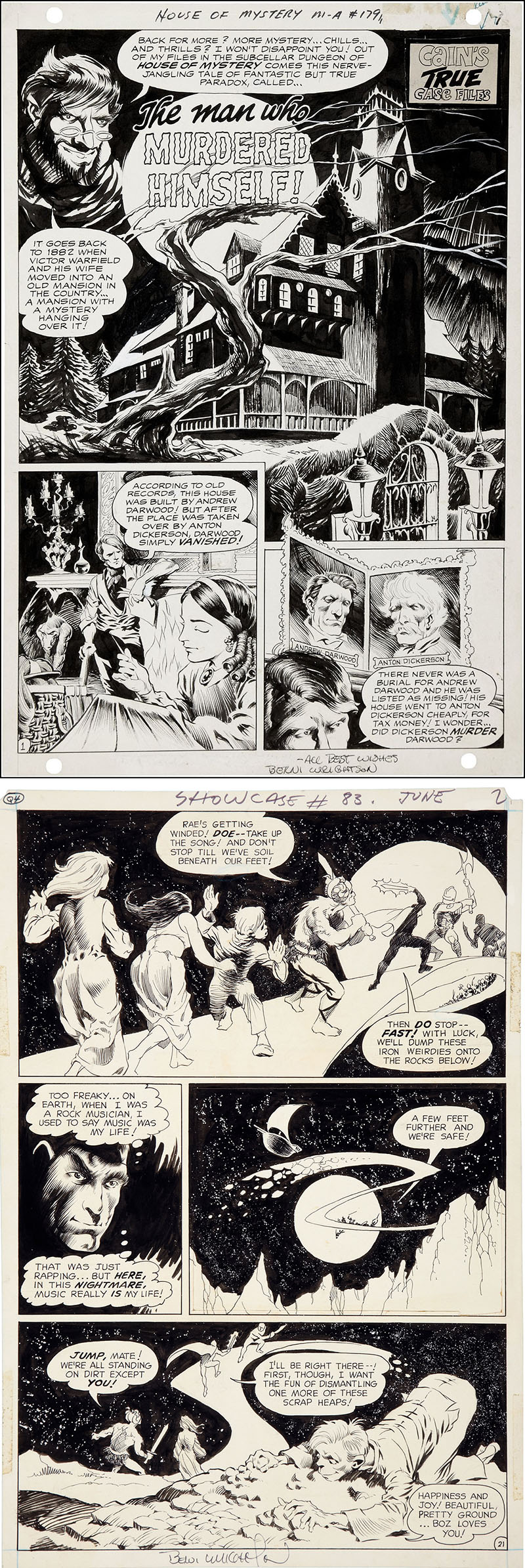

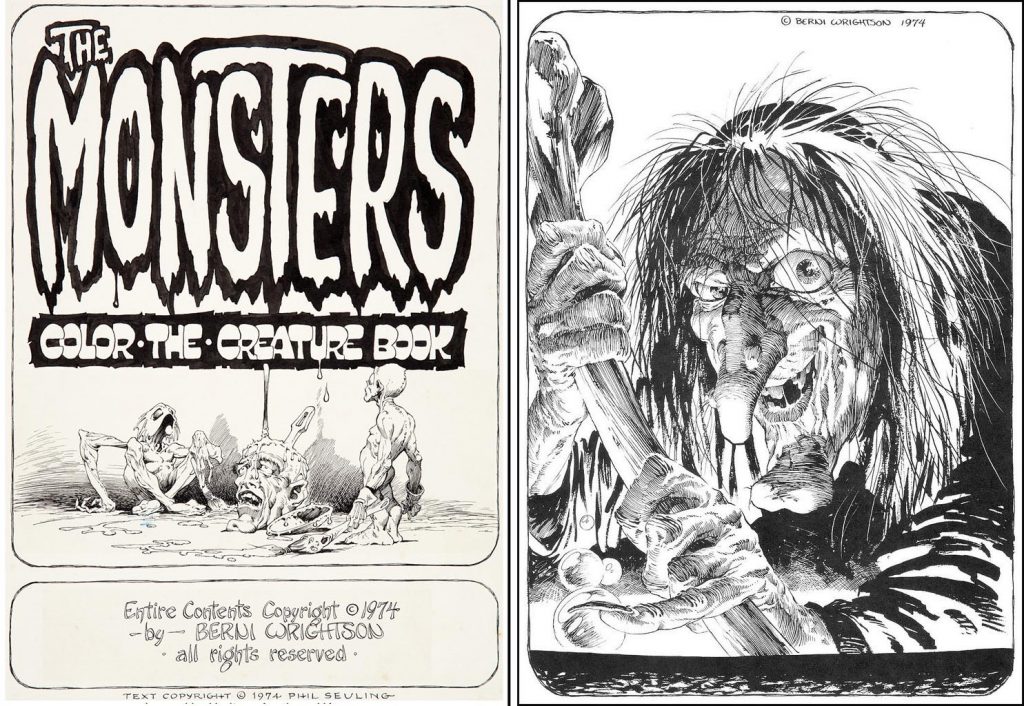

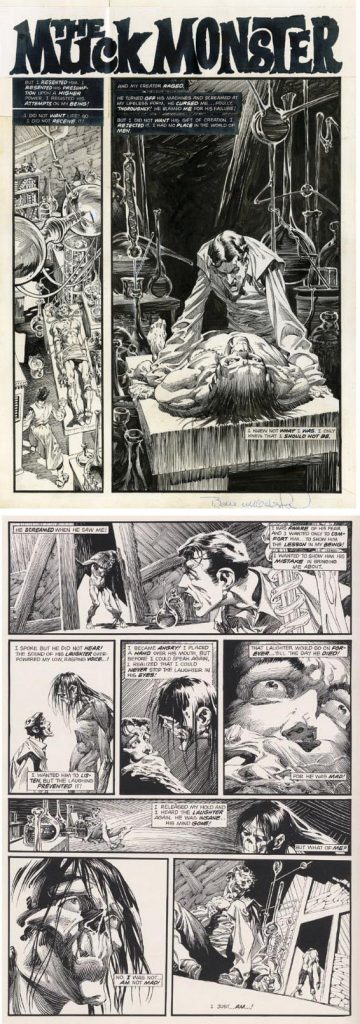

Some of that is on display in the tabloid-sized The Monsters: Color The Creature Book, a b/w pen-feast of fiends that few collectors dared to color. In Eerie #68, Bernie used a pen technique reminiscent of early 20th century illustrator Franklin Booth for a Frankenstein-like story, “The Muck Monster.” Wrightson said this and other tales “were the embryonic version of the penwork that finally showed up in Frankenstein.”

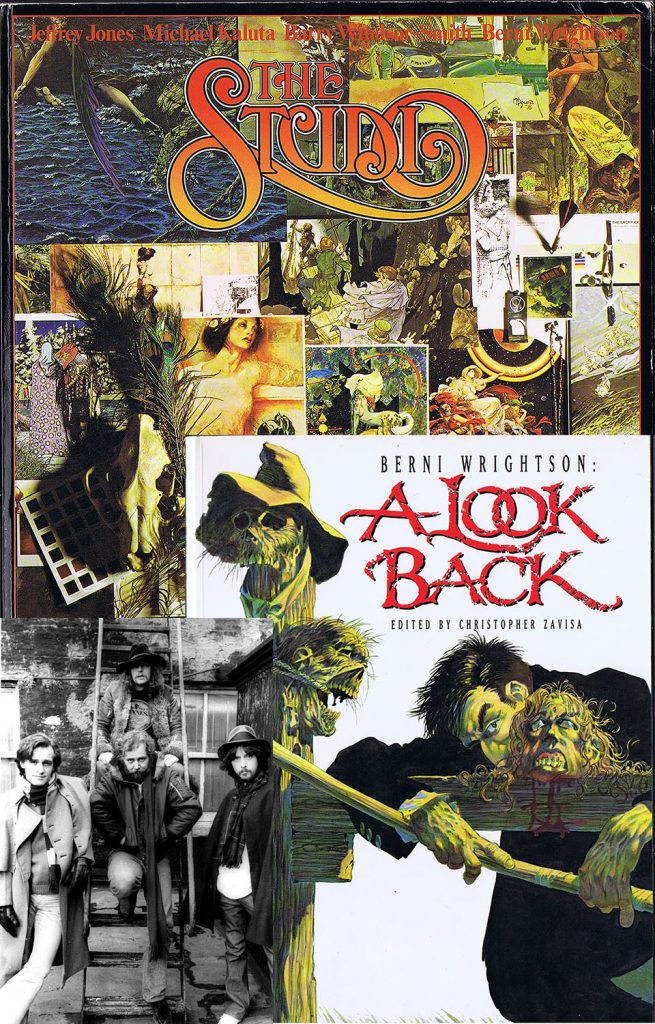

From ’76-’78, Wrightson shared a huge Manhattan space with Kaluta, Jones and Barry Windsor-Smith. They dubbed it “The Studio” and created some of their best work of the time, subconsciously inspiring and pushing each other’s abilities and talents.

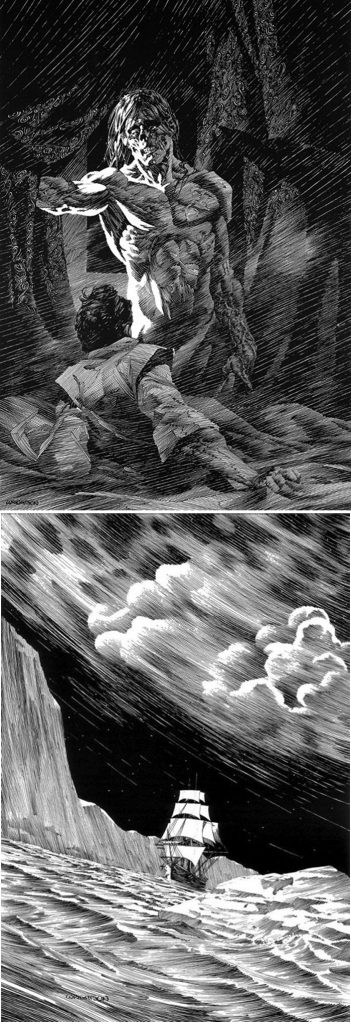

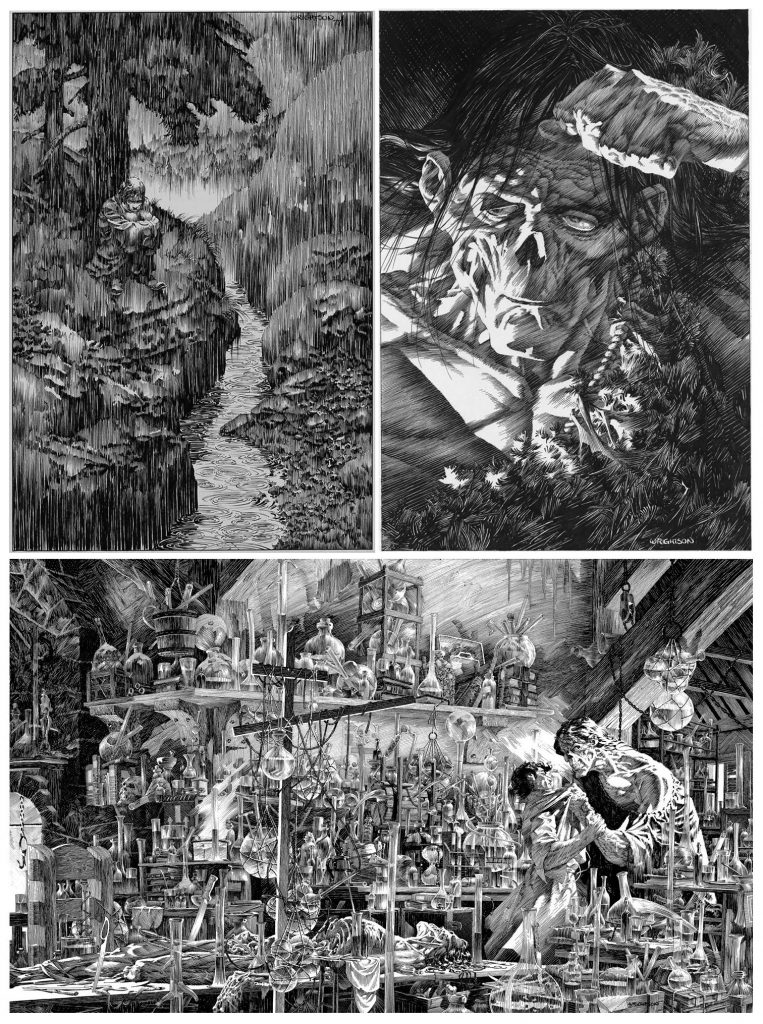

All this time, Wrightson had been working on his magnum opus, a fully illustrated version of Mary Shelley’s novel of Frankenstein. After seven years (off and on) and dozens of full-page illustrations (of which less than 50 were used), it was finally published in 1983, first by Marvel and again by others. Wrightson’s favorite author Stephen King provided the introduction. There were also limited, signed and numbered portfolios (including an unauthorized French one). The publication won awards and though not a comic book, is arguably the best single black-and-white work by any comic-book artist.

Regarding his technique, Wrightson said in 1982:

“I’m kind of aping Franklin Booth on this thing[.] I’m trying to do it all with single lines varying in thickness, to kind of imitate an old steel engraving or woodcut. So there’s not a lot of cross-hatching. There’s not a lot of that kind of pen texture. So…let’s call it an engraving technique, with a pen…after you’ve done 20 or 30 pictures, you really start getting the hang of what a line this thick is going to do when you narrow it down across the space of seven inches to a hairline. And then lay another line exactly like it, next to it. And the next one is a little bit thinner so you can get a gradation. And after a while it becomes remarkably easy to do it…it became too easy…there’s a middle period, fortunately, it’s a very broad middle period, of what I consider to be the best stuff. On the early stuff, the technique isn’t quite there, and on the later stuff the technique is completely overpowering. To me, anyway…And I don’t think I’m going to be using this technique much after this. I’m going to find something else.”

Concurrent and subsequent projects included books, limited prints, posters and portfolios, plus paperback and album covers. A multi-edition “coffee-table” retrospective, Berni Wrightson: A Look Back, edited and published by Christopher Zavisa, first appeared in 1979 with an introduction by Harlan Ellison.

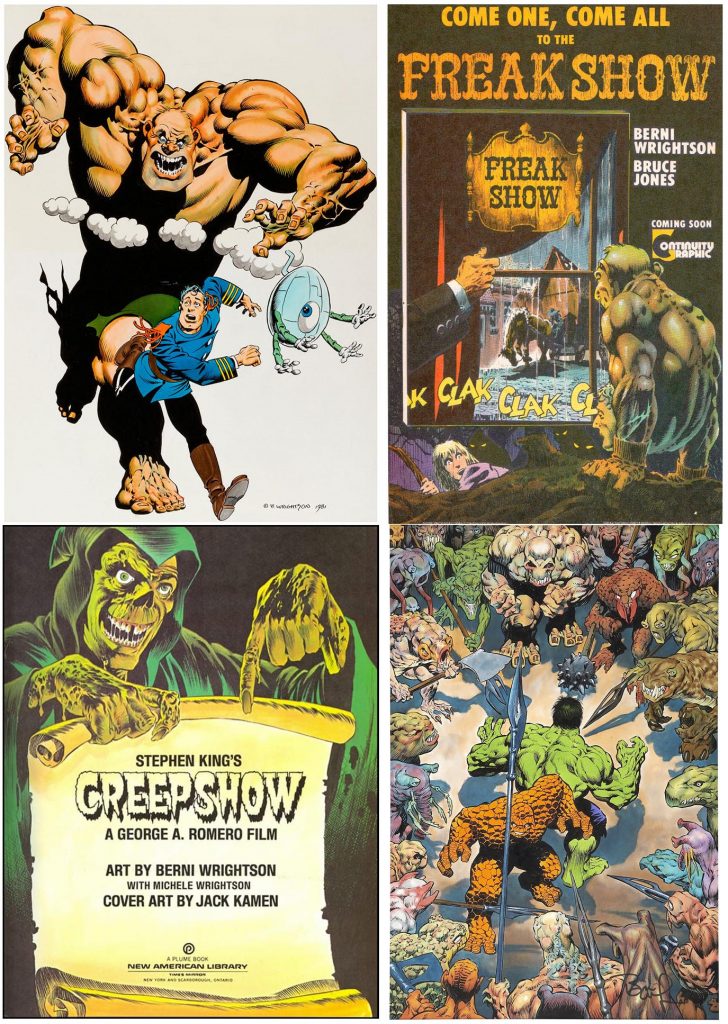

One of Bernie’s “for fun” projects (inspired by Star Wars), “Captain Sternn,” saw publication in Heavy Metal magazine and became part of their 1981 cult-favorite animated anthology. (Wrightson’s was arguably the most faithfully-adapted of all.)

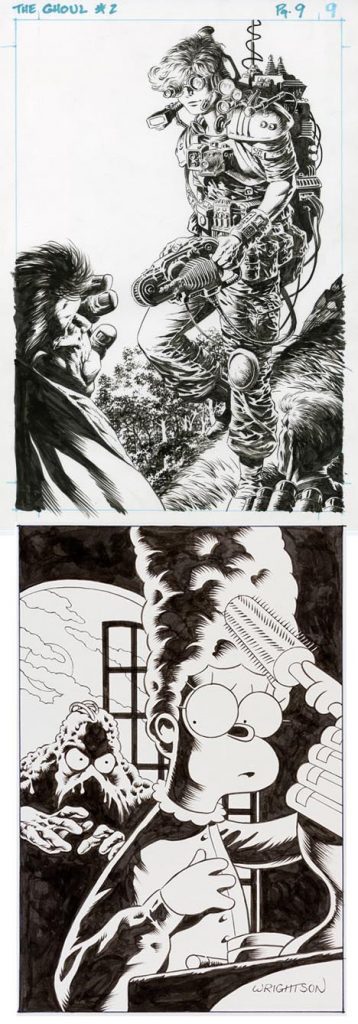

Stephen King tagged Bernie for the graphic novel adaption of the writer’s EC Comics-inspired film Creepshow (for which he also supplied some uncredited art) and the novelette Cycle Of The Werewolf. Wrightson returned to Marvel for color graphic novels like Spider-Man:Hooky and The Incredible Hulk And Thing: The Big Change and covers. Bernie forayed into film as a “creature design consultant” for the 1984 blockbuster Ghostbusters.

After souring on DC for being snubbed during production of the Swamp Thing movie around 1981, Wrightson finally came back in 1988 for mini-series like Batman: The Cult and The Weird, both written by long-time friend Jim Starlin. (Swamp Thing would go on to star in an animated and two live-action TV shows.)

After souring on DC for being snubbed during production of the Swamp Thing movie around 1981, Wrightson finally came back in 1988 for mini-series like Batman: The Cult and The Weird, both written by long-time friend Jim Starlin. (Swamp Thing would go on to star in an animated and two live-action TV shows.)

The pair also teamed up for Heroes For Hope (Marvel) and Heroes Against Hunger (DC), both benefit “jam” comics with chapters by different creators, which raised funds to help famine relief. Bernie’s cover for TV Guide in 1997 became an instant collectible.

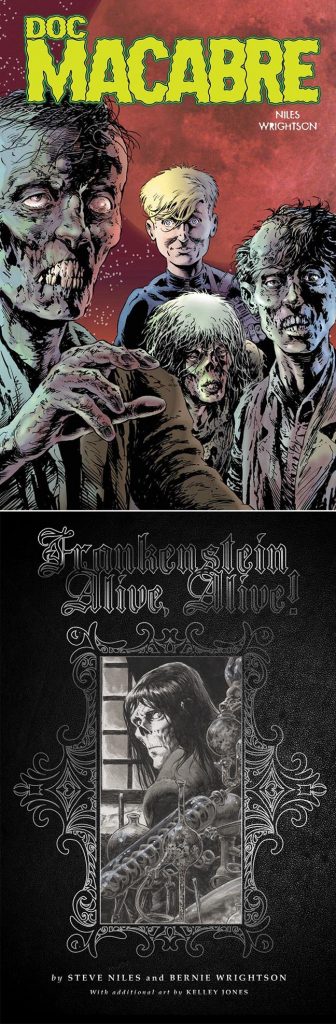

Wrightson’s 21st century projects included card game art, numerous private commissions, occasional comics, Stephen King’s The Dark Tower illustrations, and concept art/creature designs for several films including the King adaptation The Mist. He teamed up with writer Steve Niles for several mini-series comic books for IDW Publishing, including reuniting with his opus subject for Frankenstein: Alive, Alive! in 2012.

In early 2017, Bernie announced he was retiring due to brain cancer, which ultimately claimed his life on March 18, at the too-young age of 68. During his 50-year career, he received numerous accolades and awards, the last of which was the first Inkwell Awards Special Recognition Award (now the Stacy Aragon Special Recognition Award, or SASRA) in 2015, the first recipient to win both of their lifetime achievement awards.

Wrightson has influenced and/or inspired generations of artists in various media. Kelley Jones became known for aping Bernie’s style. Walt Simonson called him a “master of value,” and Neil Gaiman, who used the Wrightson and Marv Wolfman creation “Destiny” in his famous Sandman series, said Bernie’s was the first comic artist’s work that he loved. Michael Kaluta once wrote, “There’s never been, to my knowledge, a brush man that could hold a candle to what Bernie’s laid down, and…I doubt there’s anyone alive today who could top the penwork Bernie showed the world…” Oscar®-winning director Guillermo Del Toro took a 24-hour pledge of silence in tribute following the artist’s passing and wrote: “As it comes to all of us, the end came for the greatest that ever lived: Bernie Wrightson. My North dark star of youth. A master.”

Not just a master of the macabre, but a master of ink, brush and pen; of lighting, atmosphere, mood…and art itself.

Article by Inkwell Assistant Director Mike Pascale with quotes and information taken from The Bernie Wrightson Treasury (Omnibus Publishing), Bernie Wrightson: A Look Back (Land Of Enchantment/Underwood-Miller), The Comics Journal #76 (Fantagraphics Books), Comic Book PROfiles #2 (As You Like It Publications), Comic Book Artist #s 4 and 5 (TwoMorrows Publishing) and Wikipedia.